New York loves saying it supports small businesses. It says it at press conferences. It says it in budget hearings. It says it in glossy reports, task forces, ribbon cuttings, and end-of-year recaps. On paper, the city looks generous. In real life, most actual business owners never touch the help.

That gap isn’t a failure of communication. It’s how the system is designed.

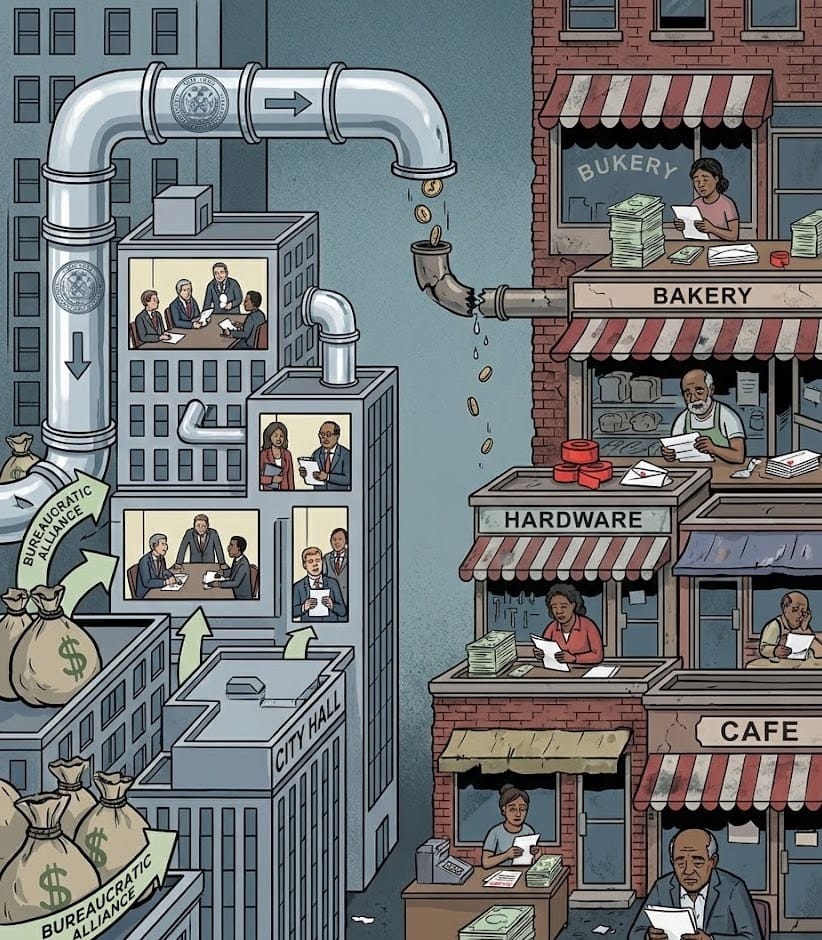

New York does not primarily fund small businesses. It funds organizations that claim to represent them, Chambers of commerce, Alliances, Development groups, Nonprofits, Consultants, Intermediaries with staff, offices, boards, logos, and annual galas. The money moves to them first, with the assumption that support will eventually trickle down to the street.

Sometimes it does. Most of the time, it doesn’t.

What happens instead is predictable. The same organizations receive funding year after year because they understand the process. They know how to apply. They know the language. They know how to frame outcomes. They know how to show “impact” in ways the city recognizes. Meanwhile, the businesses these programs are supposedly built for are too busy working, too under-resourced to apply, or never informed the money exists.

This is not corruption. It’s comfort.

Intermediaries are easy for the city to work with. They consolidate voices. They reduce complexity. They turn tens of thousands of messy, diverse, unpredictable businesses into a handful of contracts and reports. One agreement instead of ten thousand conversations. One dashboard instead of lived reality.

But simplification has a cost.

When support is filtered through organizations, nuance disappears. The loudest voices aren’t always the most affected. The most present aren’t always the most vulnerable. Policy starts responding to proximity, not pressure. Representation replaces reality.

Food businesses feel this hardest. Independent restaurants, vendors, pop-ups, caterers, and small producers operate on thin margins and fast timelines. When costs spike or revenue drops, they need relief immediately, not after a committee meeting or a six-month review cycle. But most programs move slowly, require perfect documentation, assume English fluency, financial literacy, and time that many operators simply don’t have.

The businesses that need help most are the least equipped to access it.

That’s the quiet contradiction underneath New York’s small-business narrative. Relief exists in theory, but access depends on how close you are to the system, not how exposed you are to risk. If you’re inside the room, you benefit. If you’re on the street, you hustle alone.

Intermediary organizations are not villains. Many started with good intentions. Some still do meaningful work. But over time, incentives shift. Survival becomes about sustaining the organization itself. Staff salaries. Office rent. Program continuity. Future funding cycles. Success gets measured in activity, not outcomes. Workshops replace capital. Panels replace access. Visibility replaces viability.

A restaurant doesn’t need another seminar on resilience. It needs rent relief. A vendor doesn’t need a networking breakfast. They need permits that arrive on time. A small producer doesn’t need a report written about them. They need cash flow.

The city plays along because intermediaries make the problem feel manageable. They speak policy fluently. They show up on time. They file reports. They reduce political risk. Funding them feels like action without friction.

Direct support is harder. It requires trust. It requires speed. It requires admitting the city doesn’t fully control the street-level economy. It requires designing systems around how businesses actually operate, not how funding wants to be tracked.

So, New York chooses the safer route.

Look at the numbers. NYC employs more than 300,000 workers and spends over $27 billion a year on payroll alone. Small Business Services, the agency charged with supporting the city’s economic backbone, operates on a fraction of that. Under one percent. For every dollar spent helping small businesses, tens of dollars go toward maintaining the city’s internal workforce.

This imbalance isn’t accidental. It reflects priorities.

Small businesses are inspected, fined, delayed, and regulated by multiple agencies that don’t coordinate with each other. Permits arrive late. Inspections overlap. Rules contradict. Fees compound. Time burns. Owners adapt or close. When a business shuts down, the city loses sales tax, employment, foot traffic, neighborhood safety, and cultural gravity.

Everyone understands this. And yet the structure remains.

Because the system isn’t built around outcomes. It’s built around internal continuity.

Funding intermediaries keeps the machine stable. Directly empowering operators introduces unpredictability. Builders move fast. They break rules unintentionally. They don’t fit neatly into quarterly reports. They need flexibility, not frameworks.

So instead of changing the pipeline, the city announces another initiative. Another pilot. Another advisory council. Another round of funding that rarely reaches the people it’s named after.

Ask a street vendor how many grants they’ve received. Ask a small restaurant how many relief programs arrived in time to matter. Ask a first-generation entrepreneur how often the city checked in after the photo op. The answers are consistent.

This is how cities hollow out quietly. Not through scandal, but through misalignment.

A system that funds representation more than results eventually confuses motion with progress. It looks busy. It sounds productive. It fails slowly.

The most dangerous part is how normalized this has become. Even criticism now targets the wrong layer. People argue about which organizations deserve funding instead of questioning why funding rarely reaches builders directly. The conversation stays inside the system. The street stays outside it.

Real support doesn’t look like this.

Real support reaches operators directly. It simplifies access. It respects time. It moves at the speed businesses move. It prioritizes capital, flexibility, and stability over programming and optics. It acknowledges that survival decisions are made weekly, not annually.

New York has the money. That’s not the debate. The debate is whether the city is willing to bypass comfort to create impact.

This isn’t about defunding intermediaries. It’s about stopping the illusion that funding them equals supporting small businesses. Representation is not a substitute for results. Advocacy is not the same as access.

A city that truly values entrepreneurs does not outsource their survival. It builds pipelines that put resources directly into the hands of builders. Not managers. Not messengers. Builders.

If New York wants to stop losing its small businesses, it has to stop congratulating itself for funding the ecosystem around them. Support that never reaches the street isn’t support. It’s theater.

And small businesses can’t survive on applause.

Like this? Explore more from: