That lie is now costing the city time, money, culture, and credibility.

Permits take months. Small businesses burn out before opening. Enforcement feels arbitrary. Public safety priorities change every few blocks. Nightlife is treated like a liability instead of a revenue engine. And every administration promises reform while running the same centralized system that keeps producing the same broken outcomes.

This isn’t incompetence. It’s scale failure.

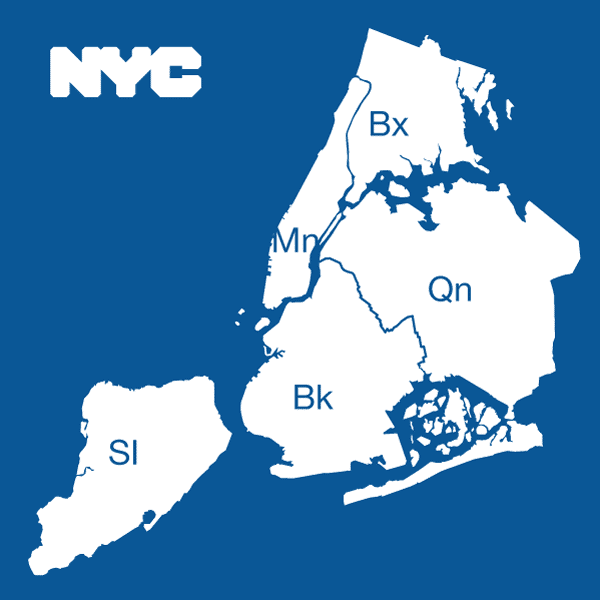

New York City is too large, too diverse, and too behaviorally different to be governed as a single unit. The boroughs already function as independent cities in every way that matters except governance.

And here’s the part no one wants to admit.

New York already has borough governments. We just stripped them of power and called it coordination.

Five cities hiding behind one mayor.

Let’s get specific.

Brooklyn has roughly 2.6 million residents. That’s larger than Chicago.

Queens has 2.3 million residents, more than Houston.

Manhattan’s daytime population pushes 3 million, with a GDP comparable to Switzerland.

The Bronx has 1.4 million residents and one of the highest small-business densities per square mile in the country.

Staten Island has nearly 500,000 residents, comparable to cities like Atlanta or Miami.

These are not neighborhoods. These are major cities.

Yet all five answer to one mayor, one budget, and a web of centralized agencies originally designed for a city less than half this size.

That mismatch explains almost every failure New Yorkers complain about.

Speed is the clearest symptom.

According to NYC Comptroller and Department of Small Business Services reports, it routinely takes 6 to 12 months to secure basic permits for food service, construction, or nightlife operations. For projects involving inspections across DOB, DOH, FDNY, and SLA, timelines often stretch longer.

Most small businesses operate with less than 90 days of cash runway. This means New York’s permitting system kills businesses before they exist.

This doesn’t happen because inspectors are lazy. It happens because decisions are centralized, standardized, and disconnected from local reality.

Everything funnels upward. Nothing moves laterally.

Borough presidents exist. They just can’t govern.

Each borough elects a president. These officials know their communities. They appoint community board members. They review land use. They advocate for their boroughs.

What they don’t do is govern.

They cannot approve permits.

They cannot direct enforcement priorities.

They cannot control borough-level budgets.

They cannot oversee commissioners.

They are advisors in a system that needs operators.

Meanwhile, the real authority sits with citywide commissioners. Buildings. Health. Transportation. Licensing. Policing. All reporting up to City Hall. All applying citywide rules to wildly different environments.

This creates a structural absurdity where the people closest to the problems have the least power to solve them.

A borough-based city model doesn’t invent new government. It activates the one that already exists.

Borough presidents become borough mayors.

Agency commissioners gain borough-level counterparts.

Citywide departments become shared-service authorities.

This is not fragmentation. It is delegation.

Enforcement proves the case better than theory.

In 2023 alone, New York City issued tens of thousands of violations related to food service, vending, sidewalk usage, and noise. Enforcement was not evenly distributed.

Outer boroughs consistently saw higher enforcement intensity per capita, particularly in working-class neighborhoods with informal or semi-formal economies. Manhattan, by contrast, benefited from higher tolerance where violations aligned with tourism or corporate interests.

Noise complaints follow the same pattern. According to NYC Open Data, complaints are heavily concentrated in nightlife-heavy neighborhoods, but enforcement outcomes vary widely based on borough, precinct, and political pressure.

This is not equity. It is bureaucracy reacting to volume, optics, and complaints rather than harm.

Borough-level commissioners would fix this immediately.

A Bronx Health Commissioner could prioritize compliance assistance and education for small operators rather than punitive fines that shut them down.

A Brooklyn Nightlife Commissioner could regulate late-night activity as economic infrastructure, not disorder.

A Queens Planning Commissioner could streamline approvals for immigrant-owned businesses operating across languages, borders, and supply chains.

Right now, all of that gets flattened into citywide averages that fit no one.

Money hides where scale is too large.

New York City’s annual budget exceeds $100 billion. At that size, accountability becomes theoretical.

Residents know taxes are high. They don’t know where the money goes. Borough outcomes disappear into citywide line items and inter-agency transfers.

Separate borough budgets would end that immediately.

Each borough would raise revenue.

Each borough would spend it.

Each borough would answer for outcomes.

If Brooklyn invests heavily in nightlife infrastructure and it works, residents see it. If it fails, leadership owns it. If the Bronx prioritizes small business survival and health access, results become visible fast.

Centralized budgets protect inefficiency. Local budgets expose it.

Culture is not decoration. It is the economy.

Food, nightlife, street commerce, and informal economies generate billions of dollars annually in New York and employ hundreds of thousands. Yet citywide policy treats these sectors like nuisances to be managed instead of assets to be cultivated.

That’s why street vending reform stalls for years.

That’s why nightlife task forces issue reports instead of permits.

That’s why pop-up culture gets regulated into extinction.

Policy works when it reflects behavior. It fails when it tries to overwrite it.

Borough governance aligns rules with how people actually live.

The coordination argument is weak and outdated.

Critics claim five cities would mean chaos. Conflicting rules. Confusion.

The truth is New York already operates with inconsistent rules. They’re just unofficial, uneven, and unaccountable.

A federated city model formalizes coordination instead of pretending uniformity exists.

Transit stays regional.

Water stays regional.

Emergency response stays unified.

Housing, zoning, business regulation, nightlife policy, and enforcement priorities move to the borough level, with inter-borough agreements where necessary.

This is how every large, complex system survives. London does it. Tokyo does it. Even Los Angeles does it informally.

New York’s refusal to evolve is the anomaly.

What this actually unlocks is not abstract reform. It’s immediate improvement.

Permits measured in weeks, not months.

Clear enforcement standards.

Local economic strategies built for reality.

Real accountability.

Cultural survival.

A Bronx vendor dealing with a Bronx government that understands street food as economic survival, not defiance.

A Brooklyn operator working with regulators who understand nightlife as tax base and tourism, not disorder.

A Queens entrepreneur navigating systems built for global commerce, not Midtown assumptions.

A Manhattan administration focused on density, capital, and tourism without exporting those pressures outward.

A Staten Island government building infrastructure for how people actually live there.

This is not secession. It is modernization.

New York didn’t become five cities because of politics.

It became five cities because people solved problems locally when centralized systems couldn’t.

The streets adapted. The government didn’t.

The question is no longer whether New York is five cities.

It already is.

The question is how much longer we’ll keep pretending one mayor can run all of them while the city bleeds time, culture, and trust.

That’s State Of The Street.

Like this? Explore more from: