People think running a food festival in New York is glamorous. They see the drone shots, the crowds, the colors, the lines wrapped around a block that didn’t even know it was capable of that kind of excitement. They see the vendors smiling, the performers dancing, the families holding plates like trophies, and they assume there’s some magical backstage calm where the producer sits in a folding chair, legs crossed, sipping iced coffee like a benevolent king watching his empire hum. I wish. The truth is closer to controlled chaos, a pressure cooker, and a sprint through a minefield—every single time—no matter how long you’ve been doing it. And I’ve been doing it almost a decade.

People want the celebration, but nobody wants to build it. New York loves a spectacle but has no patience for the labor that makes it possible. Everyone expects the festival to exist the way they expect tap water to run: forever available, always flowing, and somehow free. They don’t see the 4 AM mornings, or the weeks spent negotiating with agencies that don’t talk to each other but somehow all need the same document “immediately,” or the conversations with vendors that swing from excitement to anxiety to prayer in one phone call. They don’t see the days when a generator dies at the exact moment a line hits fifty people, or when a vendor calls in sick three hours before gates open, or when a staff member vanishes because they “went to get napkins,” which somehow turned into a spiritual journey.

Everyone thinks they understand what it takes until they try it themselves. And then they quit. I’ve seen dozens of people attempt their own event after attending one of mine. They leave inspired, energized, convinced they found the cheat code: “How hard can it be? It’s food and music.” Then they hit their first insurance quote and ghost the entire idea. Or the park permit. Or the sound permit. Or sanitation. Or the NYPD detail. Or the invoice from the staging company that charges more than a four-bedroom in the Hamptons. They don’t even get to the part where they have to manage a hundred personalities that all think their booth needs to face Mecca and get electricity, shade, a spotlight, and a guaranteed crowd before the gates open.

People love telling you how to run an event, but the only people who ever really understand the work are the ones who’ve done it—and most of them don’t stick around long enough to talk about it. The city, for all its pride in being the “capital of culture,” is not always your partner. Sometimes it’s your supervisor, and sometimes it’s the wall you crash into. The hoops aren’t always rational. They’re not malicious, either they’re just… New York. A tangle of departments asking you to deliver magic but refusing to admit that magic requires cooperation. I’ve had agencies ask me for things that don’t exist, then blame me for not providing them. I’ve had people tell me “your crowd is too big,” like that’s not the entire point of building a cultural platform. I’ve had nights where I spent more energy navigating the city than navigating the actual event.

People love you until something goes wrong. That’s the part nobody warns you about. You could run a flawless event for three hours straight, six thousand people eating, laughing, dancing, connecting, and the moment a speaker crackles or a trash can fills faster than expected, suddenly you’re the villain. Even when the issue has nothing to do with you. A vendor that didn’t bring enough product? Your fault. A power strip someone unplugged because they wanted to charge their phone? Your fault. A line too long because New Yorkers refuse to show up before 7 PM even though gates open at 4? Absolutely your fault. I’ve learned you can be on top of the world at sunset and the devil by moonrise. You develop thick skin or you leave.

And the money? Let’s talk about the money. Because people assume this is a gold mine. “You must be killing it,” they say, pointing at crowds that cost tens of thousands in production to even get through the gates. Security, sanitation, insurance, DJ, stage, city fees, rentals, light towers, restrooms, staff, marketing, payroll, power, barricades, fencing—it adds up. Then you add the New York factor, which is basically a tax on existing. I’ve had people show up to a free event with entire picnic setups and then complain about vendor prices. I’ve seen nutcrackers appear out of nowhere like contraband spirits designed solely to wreck a vendor’s margin. I’ve seen people bring their own food, their own drinks, their own chairs, their own entire dining room set, and then ask for more seating. This city is wild.

Most people who work these events, unless they’re lifers, treat it like a stepping stone. And that’s fine. This isn’t a monastery. But the few who take it seriously, who show up early, who keep their composure under pressure, who remember that reliability is a rare currency in this business, those people become priceless. You keep them close. You don’t let them drift. And you pray nobody poaches them.

Marketing these events is its own war. The algorithm is a trash fire. You could feed half the borough and still get comments like “When is this?” even though the event details are in the caption, the poster, the bio, and the cityscape behind you. You deal with trolls, critics, people who assume you’re a millionaire, people who assume you’re a nonprofit, people who assume you owe them something simply because they live within a five-mile radius. And you deal with the chaos of platforms that reward drama over community.

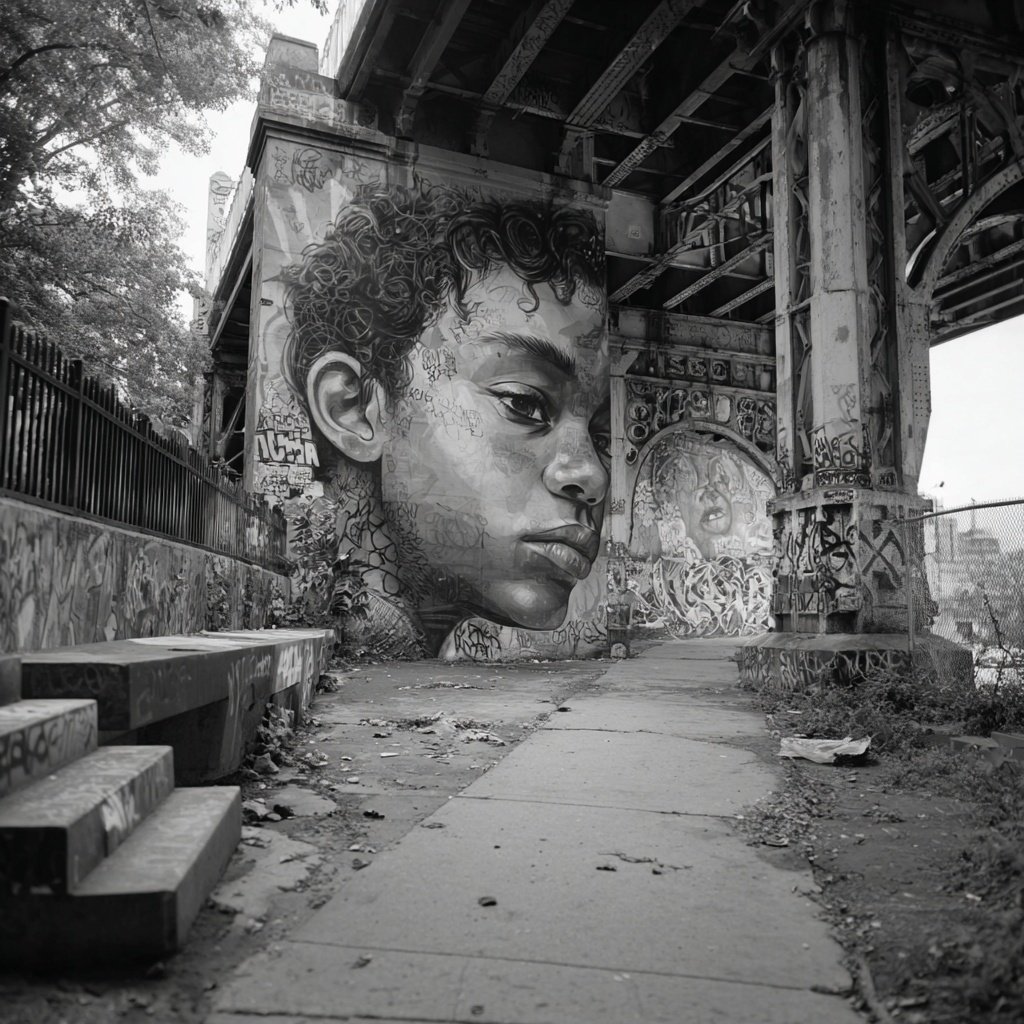

But here’s the strange thing. The thing that makes all the insanity worth it. The community. The real one. The vendors who show up with heart, hustle, and recipes that traveled continents before landing on a street under the arches in Harlem or a plaza in the Bronx. The immigrant families who treat a six-hour market like their Super Bowl. The regulars who bring their kids every month and tell you, “This is the only time we feel the city is ours.” The collaborations. The smiles. The stories. The sparks of culture you can’t script, can’t manufacture, can’t fake.

That’s why I still do it. Not for the glamour or the press or the illusion that this is some golden goose. I do it because New York needs spaces where small businesses can become big ones, where neighborhoods can become families, where cultures can cross without permission. I do it because somebody has to hold the line between community and corporate takeover, between culture and content, between authenticity and the machine.

I do it because the city is hungrier than ever. For food, for connection, for identity, and someone has to feed it in a way that feels like New York and not like a franchise rollout.

I do it because the magic isn’t gone. It’s just expensive, exhausting, and almost impossible.

But when it hits… when the crowd roars, when a vendor sells out, when a kid dances, when an elder nods in approval, when the aroma of twenty countries sits in one airspace. You remember why you started.

And you remember why you can’t stop.

Like this? Explore more from: