One New York descends the stairs at 17 Mott Street because they saw a travel host do it, or because they’re chasing the nostalgic high of salt-and-pepper chicken and egg rolls after 2:00 AM. The other New York has been walking down those same yellow-tiled steps for decades, often with a shift ending behind them or a long night ahead. They don’t look at the photos on the wall. They don’t need the kitsch. Wo Hop has always belonged to the second city.

The room is a basement time capsule. The fluorescent lights are unforgiving. The service is a masterclass in efficiency over empathy. Most first-timers head for the fried specials—the heavy, golden-brown dishes that photograph well under a phone flash. They are fine. They are the gateway. But if you watch the guys who have been eating here since the 70s—the ones who nod to the staff without saying a word, a different order hits the table.

Jumbo Shrimp with Lobster Sauce.

This isn’t the gloopy, translucent takeout version found in a cardboard box in the suburbs. This is the Move.

It is a dish of structural integrity and old-school Cantonese-American technique. It is a sea of fermented black beans, minced pork, egg blossoms, and garlic, anchored by shrimp that actually have snap. This is functional luxury. It’s the kind of food that provides a specific, heavy warmth that fried food can’t touch. It is a dish meant to be eaten over a mountain of white rice, designed to sustain someone through a double shift or a freezing Manhattan winter.

In the history of Chinatown, lobster sauce is a pillar. It’s not a trend; it’s a survivor. It’s a dish that demands the kitchen knows how to balance salt and silk. If the heat is too high, the egg clumps. If the black beans are handled poorly, it’s a salt bomb. When it’s right, like it is at Wo Hop, it carries the weight of the neighborhood’s history. It tells you the kitchen isn't just frying things for tourists—they are cooking for the people who live here.

At Wo Hop, the lobster sauce doesn't care about your "hidden gem" caption. It’s grey-ish, beige, and unapologetically messy. It doesn’t photograph cleanly. It doesn't sell itself to the uninitiated.

That’s why it’s the ultimate regular’s flex.

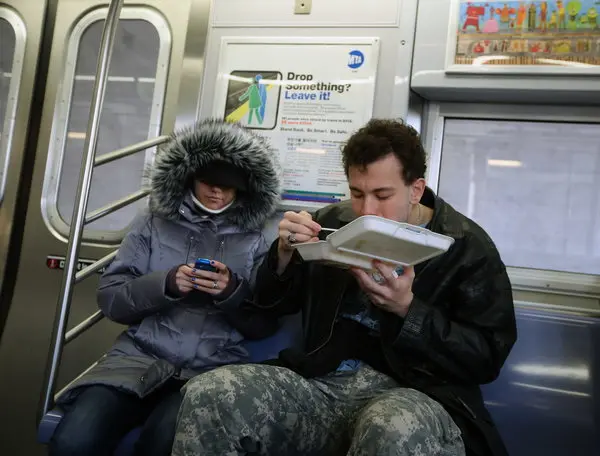

The people ordering the shrimp with lobster sauce aren't there for the "Chinatown aesthetic." They are off-duty taxi drivers, multi-generational families from the surrounding tenements, and the hospitality workers who know exactly which burner has the most "wok hei." You hear the clatter of heavy ceramic, the hum of the ventilation, and the sound of people eating with a deadline.

The fried chicken is the front door. The Shrimp with Lobster Sauce is what tells you the house is built on a foundation of real technique.

New York food culture loves to reinvent the wheel. Every week there’s a new "concept" in a glass-box building. Wo Hop stays in the basement. They don’t need an rebrand. They feed the people who keep the city’s gears turning.

Ordering the lobster sauce isn’t about being "different." It’s about understanding the code. It’s about trusting the dish that has remained unchanged while the skyline above it transformed.

If you want to understand how Chinatown really survives, sit in the back, ignore the "famous" fried wings, and watch what the guy in the corner is pouring over his rice.

At Wo Hop, that plate has always been the Move.

Like this? Explore more from: